Pahingi ng Amoxicillin: Preliminary Ramblings on Being a Community Doctor (and some other drama)

|

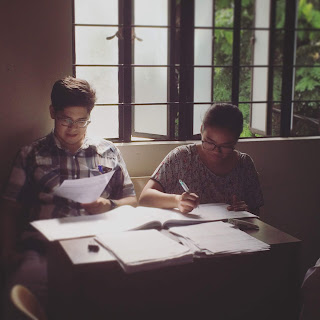

| Can't escape the paperwork. |

It's weird for me to be sitting at my keyboard, typing up something that isn't going to be submitted as an academic requirement. I've been away from blogging for so long. It's painful to restart. I'm constantly rereading these sentences as I create them, parsing each one before forcing myself to move on to the next one. Editing and editing. I have three unpublished drafts lined up in my Blogger dashboard, each one maybe 3 paragraphs long. Every time I go to my Blogger to begin writing, the sight of these drafts reminds me of my countless aborted attempts.

What's with the melodrama?

A lot has happened in my life that I need to write about, but haven't been writing about because of the sensitive nature of the subject.

Ooh, sensitive how?

To put it vaguely, my stories aren't just my own. They're my patients', too, and I can't just share them online without asking them first.

Boo.

I know, ethical technicalities suck. And there is a lot I need to catch you guys up on... A lot.

Then just tell us what you can!

Fine. Okay so first of all, I got accepted into this new internship track at ASMPH called Community Enhanced Internship Program (CEIP). As the name implies, the program involves a longer community rotation than the regular internship. Hold on to your coffees guys, it's gonna get pretty technical from here.

I came here for juicy feel-good emotional writing, not for a lecture!

Yeah yeah yeah we'll get to that. So, a two-month rotation in a community is a regular part of any medical internship in the Philippines. For non-Ateneo interns (i.e. those who have completed 4 years of med school and graduated with an MD but who have not taken the board exams yet), their community of choice is dictated by the hospital that they intern at. On the other hand, regular ASMPH interns (i.e. fifth-year medical students who have not yet graduated) rotate at the health centers in Payatas, Quezon City.

Mmhmm, skip to the juicy stuff.

CEIP interns (that's me and 11 other people) rotate at a health center in Quezon City for six months (health center name withheld for privacy). We spend half of our internship year in the community, and half in the hospitals. Not to get ahead of myself, but this is a pretty radical change from the standard internship track. I don't know any school that has done this before, and I'm really proud of ASMPH for their decision to innovate on the standard medical internship. The new community track was borne out of the recognition of the immense potential of primary health care centers to become areas for education for interns. And the recognition that you don't really need all those 24-hour duties to become a good doctor.

|

| Blurry picture of me and my co-interns grabbing a bite at one of the many pares stops in the neighborhood. |

What's a health center?

I'm glad you asked, imaginary-second-voice-person-doubling-as-a-really-convenient-literary-device. I, too, had no idea what a health center was until I actually set foot into one for my college immersion. And that's because as upper-middle-class citizens, we never really have to set foot in them because we can afford private care.

Put simply, a health center is like a clinic that's run by the city government. You know how when we're sick, we go to our suki doctors at their office in a mall or in a hospital? And when we're done with the consult, we pay the consultation fee and leave? We actually have the option of accessing free doctors' consults (along with other health services) by going to our local barangay health center (seriously, every barangay has one). Aside from free check-ups, you can also get free medicines, free laboratories, free contraceptives, and free immunizations.

What the hell? All this time I've been paying for those basic health services when I could've just gotten these things for free at my health center!

Yeah what a scam, right?

Not really! Take my word for it, health centers are generally not a nice place to be. Not only are the spaces hot and crowded, the supply of medicine is erratic, and the line to see a doctor is way too long. You can arrive there at 6 am and be seen by the doctor at 10 am.

WTF that's ridiculous!

I know! The systems are inefficient AF. Getting registered at the front desk can take hours. Afterwards you'll end up standing in line for another hour to get your vital signs taken. Once that's done, you have to wait another hour for your name to be registered in an online database. Imagine having to wait this long in a hot, crowded center, surrounded by coughing tuberculous patients, screaming babies, angry lolos and lolas, and (sometimes) even angrier health center staff. I really don't mind shelling out 500 bucks if it means waiting in a comfortable air-conditioned room, where tuberculous patients and screaming babies are far, far away from my mind.

I get it. But what's the reason behind the inefficiencies?

Excellent question. I can't speak for all health centers, but aside from the super slow internet speeds, I have noticed that workers don't seem to be motivated to do their jobs. I'm guessing it's because they're either being paid too little or not being paid at all.

One of the things that surprised me most in the health center is the existence of community health volunteers, or CHVs. CHVs are the good people who do the back-breaking labor of going from house-to-house checking on all the members of the barangay to see if they're getting the medications they need. When they're not roaming around the barangay, they're stationed at the health center front desk, registering patients who are seeking consult for the day. Anyway, as the name implies, they are volunteers who do all this work and receive no compensation from the government.

Imagine doing all that work for no money! These are people with families to feed! How- no, why they continue to do what they do remains such a mystery to me.

So how's your experience been so far?

This is a really crummy question to end the blog post with but I need to wrap it up quick or else this post will end up as my fourth draft in a row.

I've grown so fast in ways I never could have imagined. When you're interning at a health center, you're pretty much considered a doctor there, despite not yet having a license. The transition from my previous work as a clerk to my current work as an actual doctor is jarring. I mean, god. It was only a couple of months ago that I was fetching bedpans for the pregnant mommies in VKMC and running around the hospital delivering blood samples from the wards to the laboratory. Now, I manage patients on my own. Do my own interview, physical exam, make my own diagnosis, and then send the patients away with a prescription that I write and sign (alongside the name and license number of the senior health center doctor). Legit doctory stuff.

People treat me so differently now. I remember as a clerk, I was lower than bacteria on the hospital food chain. Some nurses and patients would be so mean to me. There's just something about wearing an all-white uniform that makes you seem like prime target for being bossed around and treated like sh*t. You greet your seniors good morning, and in return they can't be bothered so much as to make eye contact with you or even breathe in your general direction. If you're in someone's walking path, you have to get out of the way and apologize for taking up space. For merely existing. Coming into clerkship, your monitors will tell you you're a valuable member of the healthcare team but that's just a straight-up lie.

In the community, you are one of the freaking head honchos. You're the boss. When you walk into the health center, everyone greets you good morning. When you're walking in a crowd, the crowd makes way to give space for you. The crowd apologizes for getting in your way. When you speak, people listen. My God. It's weird but at the same time, weirdly satisfying.

It's also part of the reason why I dread going back to the hospital, which I'm going to be doing on Monday. From being the queen, back to being an intern. From being a doctor to being a student. Stepping down from power is such an emotional let-down but it's a good exercise in learning to humble yourself all over again.

|

| I have a collection of bus photos from each bus trip I take to the center. This one was taken on a stormy day. |

And that's one of the things I'm learning is really important when you're a community doctor: humility. Sometimes I catch myself feeling resentment or anger towards a difficult patient, and trust me there are a lot of those in the communities. I get frustrated too often. At patients who self-medicate with antibiotics as treatment for their blood pressures. Patients who still have a very poor understanding of their condition even after all the saliva and oxygen you've expended in trying to explain it to them, over and over and over. Patients who think it's okay not to go to the ER for an actual emergency situation. Patients who are in urgent need of medicines that are not available at the center, but have no money to actually pay for them. I get frustrated too often, and I have to keep reminding myself to stay humble.

Who am I to get mad, to raise my voice? These patients are poor and uneducated; most of them haven't even reached Grade 3, while I've gotten through college and now will make it through med school. I get to eat three square meals a day, while they ponder if they can earn enough for this Sunday's dinner. Clearly, I am coming from a position of privilege while they are coming from a world of disadvantage. Who can blame them for not knowing how to use antibiotics, or not understanding what's going on with their bodies, or not buying the medicines I prescribed?

To be a community doctor is to receive daily lessons in humility. We are there providing a service, not doing these patients a favor. We learn from them as much as they learn from us. We are no better than them; we are equals, and every day is a struggle to make them see it that way too.

More than humility, each tiring day is a lesson in love. It takes a lot of patience to handle the volume of patients coming in to see you. It takes a lot of kindness and understanding to help them understand and take control of their own conditions. To nurture, encourage, and empower. I never expected community medicine would be this hard. But despite the frustrations and fatigue, I take pride in the work that I do. I take pride in the love that I give.

Good job! Great experience! Very nice write-up!

ReplyDeleteKeep it up!Serve the community, Bahala na si Lord sa yo! ��

Funny you take a picture of every time you ride a bus! :) Sakit.info

ReplyDelete